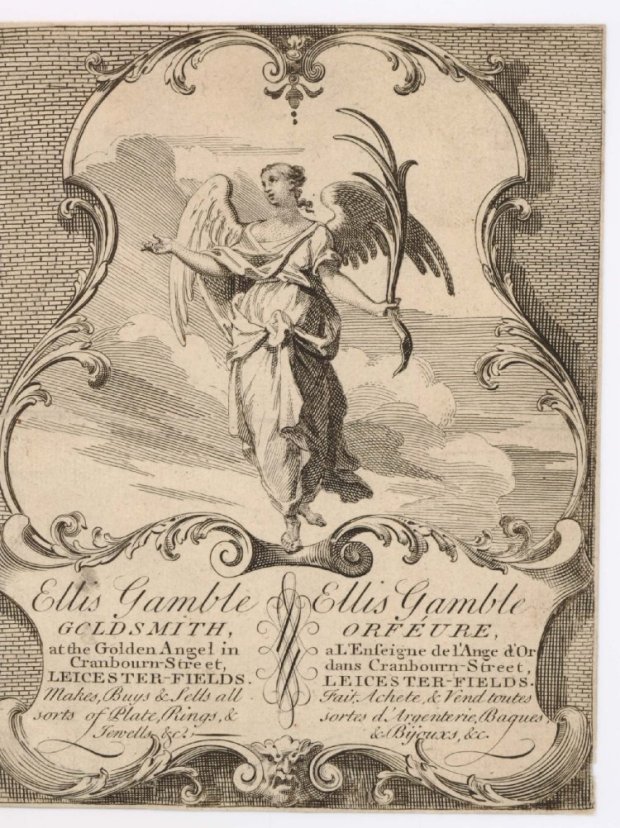

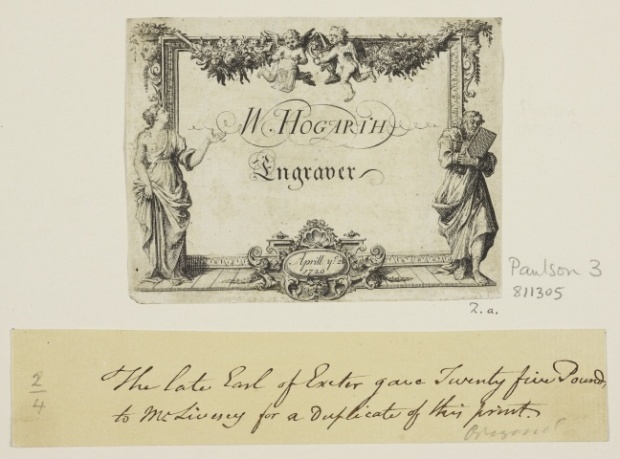

We are celebrating the craftsmanship of William Hogarth born on this day in 1697 (10th November). Hogarth was born to Richard Hogarth, a schoolmaster and Anne Gibbons who came from a working class background. At the age of 14 in 1714 Hogarth was apprenticed to Ellis Gamble in Leicester Fields as an engraver.

Ellis Gamble was a gold and silversmith who was in partnership with silversmith Paul de Lamerie from 1723-28. Hogarth started by mainly engraving trade cards, however he never finished his apprenticeship but continued to experiment with engraving as an independent engraver for copper plates.

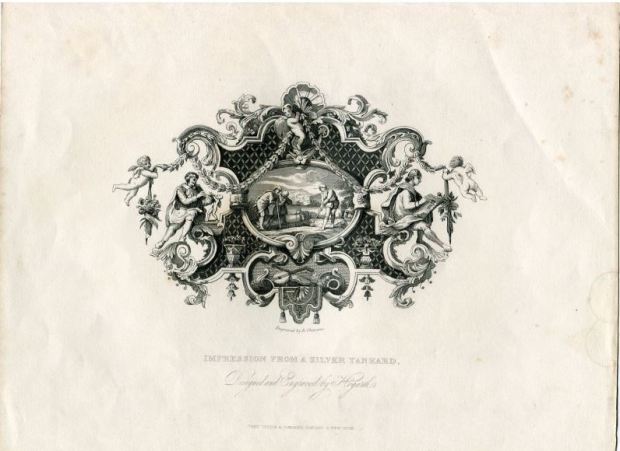

He experimented with designs and his early commissions included works for book illustrations, single prints and cards. Paul de Lamerie was one of the greatest silversmiths working in England in the 18th century. The son of Hugenot parents he came to London as a small child fleeing prosecution in France. Around 1720 de Lamerie started working with Hogarth whom he met whilst he was working under Ellis Gamble. The ‘Hogarthian’ style of engraving had a huge impact on the pieces designed and made by, not just de Lamerie, but most other silversmiths from this period. Exceptional engraving such as Hogarth’s added another dimension of craftsmanship to a silversmith’s work helping to create pieces of the highest quality and design.

In 1720 Hogarth enrolled at the John Vanderbank Art Academy and was taught painting by James Thornhill from around 1726. Hogarth is best known for his series of paintings depicting satirical modern moral subjects. Hogarth sold engravings of popular scenes on subscription. Most famously series such as Marriage-A-la-Mode, The Harlot’s Progress (1731) and The Rake’s Progress. Harlot’s Progress was about the life of a prostitute and was very different to anything else that had been produced up until this date. Rake’s Progress shows the decline of a young man into a life of drinking and immoral behaviour.

Oil on canvas

This tea caddy was engraved with the coats of arms by Hogarth, after a design by Ellis Gamble. The same coats of arms appears on a silver-gilt spoon tray by de Lamerie which suggests that this caddy was a part of a larger tea service.

Walpole Salver

The Walpole Salver, held in the collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum is the most famous piece of silver known to be engraved by William Hogarth. The salver was made by Paul de Lamerie between 1728 and 1729. It is a square salver on square feet with a cast and applied rim. Not only is it magnificently engraved with an intricate design it is one of Paul de Lamerie’s best known pieces of silversmithing.

The salver was commissioned by Sir Robert Walpole to commemorate his terms as Chancellor of the Exchequer. The seal roundels are supported by a figure of Hercules flanked by allegorical figures representing calumny and envy. The salver shows a view of the City of London in the background. Elaborate strapwork decorates the border which runs between masks representing the four seasons and four cartouches located in the corners. The cartouches encompass the double cipher ‘RW’, the arms of Walpole quatering those of his wife Catherine Shorter and the Walpole crest of a Saracen’s head.

Our gallery is located at Koopman Rare Art, The London Silver Vaults, 53/64 Chancery Lane, London, WC2A 1QS, please feel free to visit or take a look at our stock on our website www.koopman.art

For all enquiries please do not hesitate to call or email on:

020 7242 7624 / info@koopmanrareart.com